A few weeks ago, I visited the Brontë Parsonage Museum, a favourite literary landmark of mine. For those unfamiliar, the Parsonage Museum in Haworth, West Yorkshire, is housed in the home of the Brontë family, where the famous sisters grew up, and where they lived and wrote from 1820 until their respective deaths. It’s a place I’ve visited many times in the last decade since I moved back north. For the last four of those I’ve lived in a village just a few wild and windswept miles away across the moors that Emily Brontë immortalised in Wuthering Heights. Standing in the rooms where the sisters wrote those extraordinary books that influenced me so much as a young reader, and as a writer, and where Charlotte and Emily both died, never fails to move me.

This visit was no different, but once I had explored the original house, it was the exhibition space that caught my attention. I noticed something I hadn’t before – a selection of letters from Charlotte Brontë to her publishers.

The three letters chosen for display reveal some telling detail. They made me laugh. They made me sad. And they made me feel strangely connected to Charlotte Brontë as a young, hopeful writer, navigating the mysterious world of publishing.

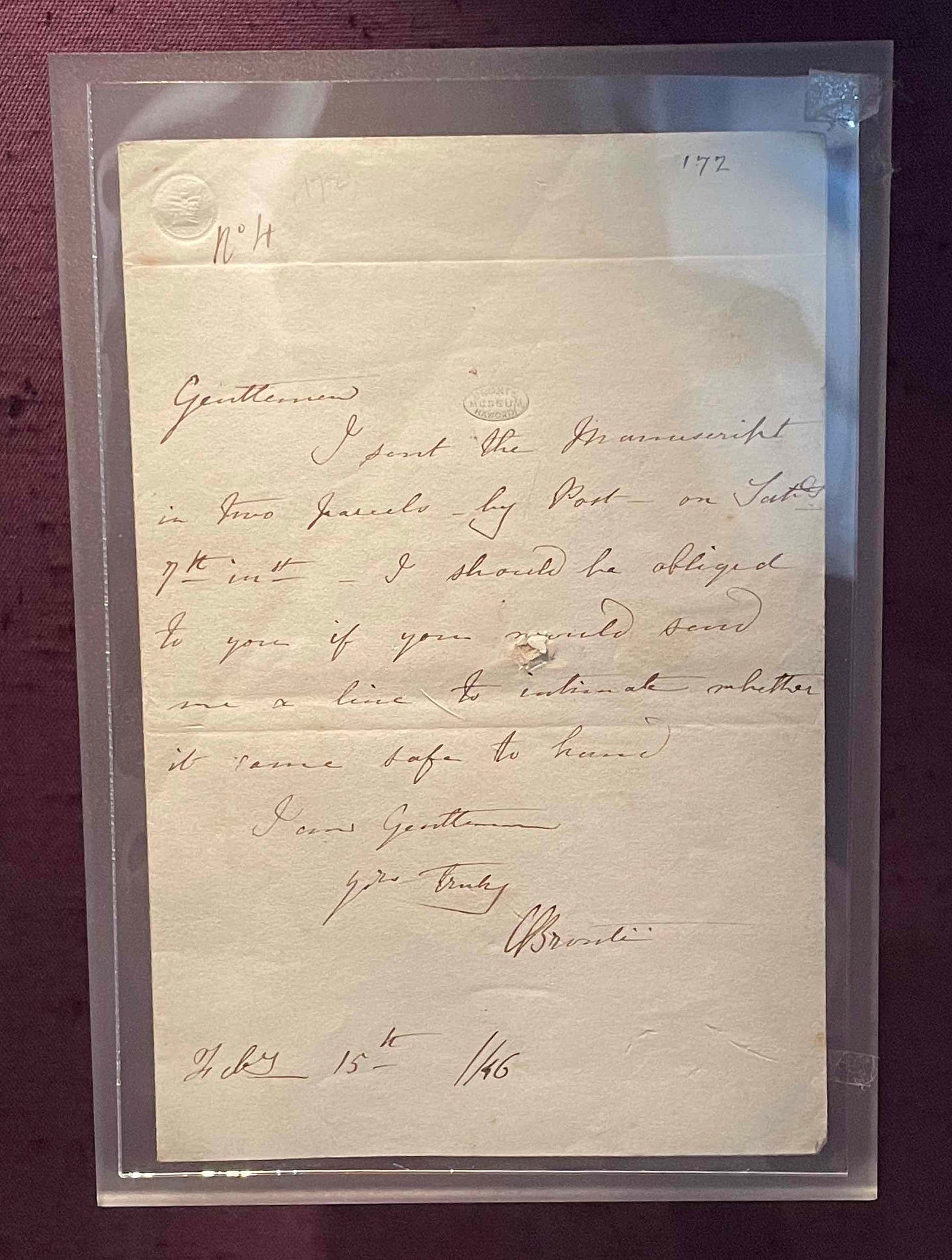

Did you know the Brontë sisters were self-publishing pioneers? Their first published work was financed from their own pockets. Poems, by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell featured work by all three sisters writing under their masculine pseudonyms. However, when Charlotte sent the manuscript to be printed, she dealt with the publisher directly using her real name, as this short note, sent on 15 Feb, 1846 to Aylott and Jones, shows…

Gentlemen

I sent the manuscript in two parcels by post on Sat 7th – I should be obliged to you if you would send me a line to indicate whether it came safe to hand

I am Gentlemen

yours truly

C Brontë

These two lines make me imagine the conversation round the famous table in the dining room where so much of the sisters’ writing took place. I see Charlotte fretting anxiously about whether the manuscript has gone missing. Anne trying to calm and reassure – it has only been a week, after all – and Emily, frankly, not giving much of a damn if it had. I imagine the pen and ink, the note dashed off impatiently, the scurry to catch the post, slipping on wet cobbles. I sense the slight irritation in that terse sign off – ‘I am Gentlemen, yours truly’ – and wonder how Charlotte would have coped with the weeks and months of waiting that have become the norm in modern publishing. Perhaps I’m indulging my novelist’s imagination, but it’s difficult not to read between these lines.

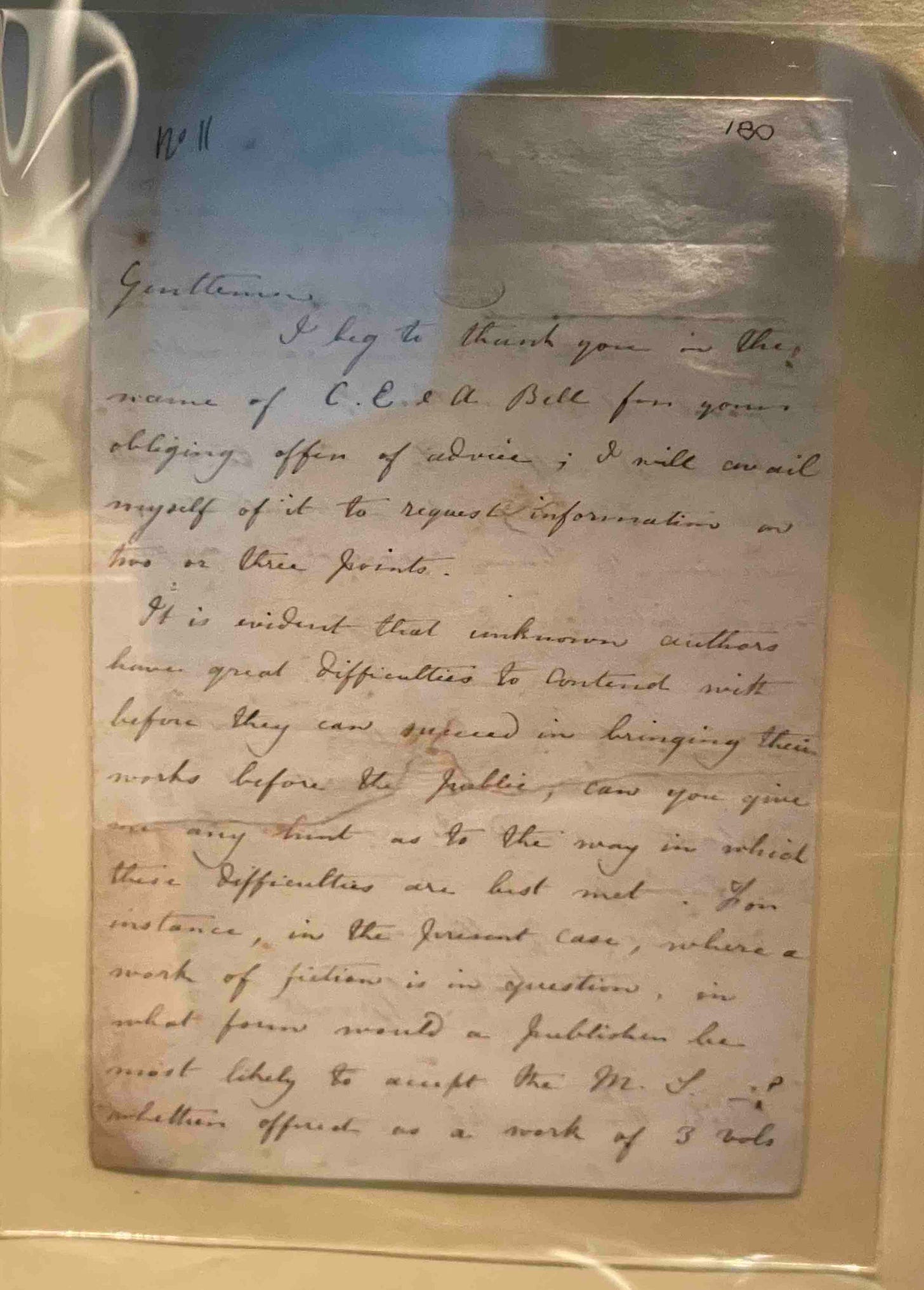

In any case, the manuscript was received. Shortly before it was published in May of that year, Charlotte wrote again to the ‘Gentlemen’ at Aylott and Jones to seek advice about publishing the novels the sisters had written.

Gentlemen,

I beg to thank you in the name of C. E. & A. Bell for your obliging offer of advice; I will avail myself of it to request information on two or three points.

It is evident that unknown authors have great difficulties to contend with before they can succeed in bringing their works before the public, can you give me any hint as to the way in which these difficulties are best met. For instance, in the present case, where a work of fiction is in question, in what town would a publishers be most likely to accept the Manuscript…

It is evident that in almost two hundred years, not much has changed. The great difficulties that Charlotte alludes to will be all too familiar with any newcomer attempting to navigate publishing gatekeepers. And the question of how those difficulties are best met? Therein lies the question in the heart of every hopeful writer I’ve ever met.

To me, Charlotte’s determination and ambition come through here, but above all I’m encouraged by her willingness to seek help. We all need guidance from those who have walked the path before us, those who hold knowledge that we do not. I wonder how these ‘two or three points’ were decided upon. Were they a product of heated discussion between the sisters or is this all Charlotte’s doing? We’ll never know, but it’s fun to consider. (I’m also curious to read the rest of this letter and know if Charlotte ever received a useful response, or were Mr Aylott and Mr Jones simply too busy to reply, her letter left to languish beneath a pile of more pressing correspondence.)

Famously, Poems, by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, only sold two copies and was quickly relegated to the literary dustbin.

Stop right there and think about that. The debut work by three of the most groundbreaking and celebrated writers that England has ever produced was a big fat flop. I’ll just leave that there.

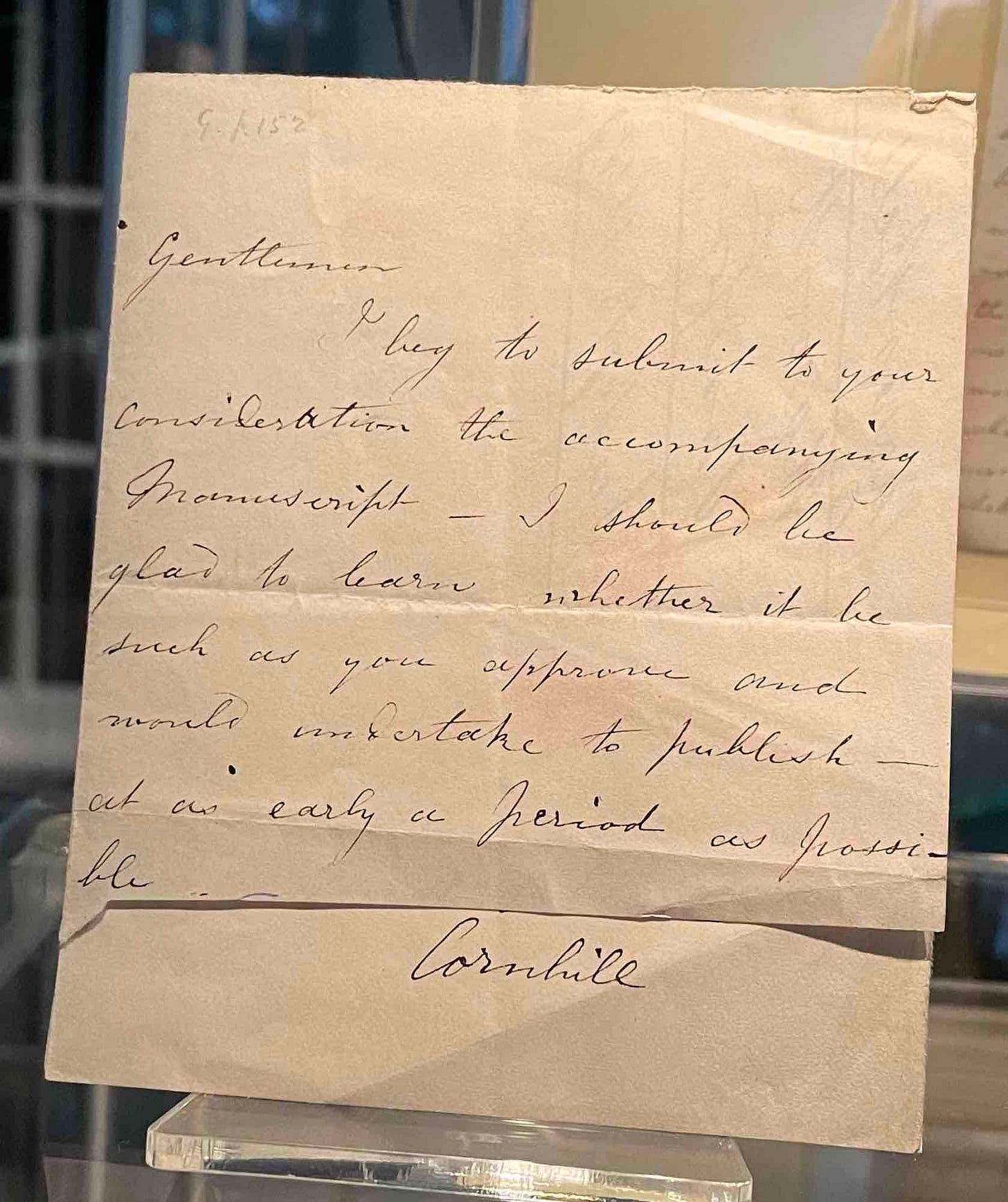

The third letter that drew my eye was written a year later – to Smith, Elder & Co, another London publisher, to which Charlotte sent her first attempt at a novel, The Professor.

I beg to submit to your consideration the accompanying manuscript – I should be glad to learn whether it be such as you approve and would undertake to publish – at as early a period as possible.

Ah, the querying process. These days, writers spend hours workshopping elevator pitches, condensing our stories into synopses that suck all the subtlety and life from them, torturing ourselves over minutely crafted, individualised submission letters. ‘How to get a literary agent’ has become almost an industry in itself. Maybe we should give ourselves a break and take a leaf out of Charlotte’s book?

Again, I’m struck by Charlotte’s directness, a certain impatience in her turn of phrase. Could it be that she’s tired of waiting to hear back from publishers? Is she losing patience?

The Professor was turned down several times before Jane Eyre was eventually accepted by Smith, Elder & Co and published in October 1847. I’m guessing they didn’t need a two-year lead time back then. Jane Eyre was a hit. Anne's Agnes Grey and Emily's Wuthering Heights came a year later, and the rest, as they say, is history.

One final titbit. The display includes a first American edition of Emily’s Wuthering Heights, published by Harper & Brothers in 1848 and incorrectly attributed to Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë), to capitalise on the success of Jane Eyre – a sure sign that nefarious marketing practices are nothing new in publishing.

So, what can these glimpses of Charlotte’s correspondence teach us?

Essentially, nothing much had changed. Unknown writers still ‘have great difficulties to contend with before they can succeed in bringing their works before the public’.

Communication between writer and publisher has always been a source of frustration, the pace of industry at odds with impatient and ambitious authors. We can accept that early failures do not determine a career. That the fates may change at any time. That there is nothing shameful about investing in your own work or paying for a service that helps you get where you want to be. A career is built step-by-step.

We can learn that there will always be rejections and disappointments and those looking to take advantage of any success that might come our way, but that we shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help, to ask questions, and to hold publishers to account.

To me, what shines through these letters is Charlotte’s steadfast determination. Her resilience in the face of rejection, failure and seemingly insurmountable odds. I love the bold way she claims attention, even if it was, ostensibly, on behalf of others.

Perhaps it was, in fact, the persona of Currer Bell that enabled this? Perhaps, in Charlotte’s 19th century context, her positioning as merely a voice for another – and a man – was freeing. This makes me wonder how we might champion our work if we were one step removed. Might writers demand better – and more – from the industry if we were speaking on behalf of others?

Rather than finding this all disheartening, I take comfort from it. I like to think of those women, those unlikely geniuses, forging the path that so many others have followed. I like knowing that their concerns and failures were similar to my own. It’s a contrary sort of reassurance to know that the irritations and frustrations of publishing are nothing new, but something to be navigated and challenged, and – maybe – embraced. It makes me feel part of something bigger, a small cog in the history of women’s writing, a tiny atom in Northern England’s literary DNA.

P.S. If you are visiting Haworth, be sure to pop in to Wave of Nostalgia, Haworth’s award winning independent bookshop.

Ways to work with me…

1:1 Coaching & Mentoring My Writing Revolution package is my gold standard in writing support. If you’re ready to commit to your writing and work toward your writing ambitions, this is the one for you. Dedicated, personal support to get your book written. (Only two slots left for 2024)

The Inkwell Join my growing writing community on Substack for monthly workshops and interaction with me. This is a low-cost, minimal commitment way to work together and see if we vibe.

Manuscript Assessment Tailored, honest and constructive editorial feedback on your writing from me, a published author and experienced editor.

Not sure what you need? No problem. Let’s chat! Book in for a free 30-minute call.

Great post Katherine. I love the fact they self published!

I love this. There is hope in this for the yet unpublished author. If only query letters were so easy though 😄 My friend recently published a book on Anne Brontë about her life (non-fiction).